The following review was published on June 24th, 2013 in the Beverly Hills Outlook magazine

RECENTLY RELEASED

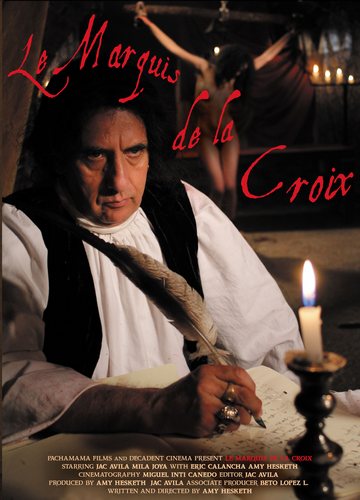

Le Marquis de la Croix

REVIEWED BY CHARLES LONBERGER

This intense and supremely focused Bolivian production, handsomely mounted by Amy Hesketh and Jac Avila with just the right visual accents and splashes of color for Decadent Cinema, is a master class in film direction, courtesy of Hesketh herself.

Largely restricted to one set, a dungeon illuminated by candle lights for its entire running time, Hesketh creates a universe out of it. Although her perspective is strictly third person, there is a psychic bond that involves the audience with what is, when all is said and done, an extended performance scene. Interestingly, through her blocking of her actors and dramatic compositional framing, she emphasizes the separate spheres her protagonists occupy in their shared experience, distancing them from each other rather than uniting them.

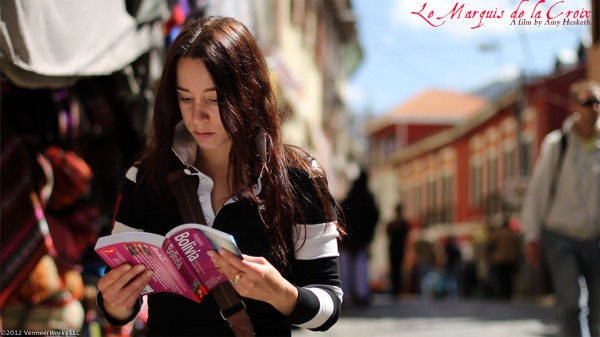

Opening her film by introducing her set, which we recognize from Maleficarum, as a museum, complete with guided tour, with two of the tourists assuming the identities of the film’s protagonists (which suggests the film itself is a fantasy of a tourist, played by Hesketh herself as a member of that tour). Hesketh takes us back in time with a simple clean edit and doesn’t look back, although she concludes her film with a witty epilogue that exhibitionistically reminds us of her own familiarity with a central prop in the production, an epilogue that shows, via drugged tea, that the Marquis of the title still has his adherents.

This is because the central theme of Hesketh’s own Spanish language script is the very heart of darkness, as it portrays “the hour of destruction,” with one human being, an accused criminal and gypsy, sold to another to be “dominated, tortured and executed.” In her script, Hesketh portrays murder as an ultimate erotic experience. This control of one person by another, previously portrayed more gently in Hesketh’s earlier relationship drama, Sirwinakuy, is, at its core, brutal, though it is here introduced obliquely, with the Marquis assuming “responsibility” for the gypsy he has bought and, by so doing, saved from the guillotine.

Very cleverly, but essentially, the script provides a context for specialized but enduring Fetishes, involving crucifixion, rack and foot torture, to be showcased

The film gives us breathing space slightly in an opening sequence through exterior footage of the Mestizo Baroque architecture of Bolivia, which in Maleficarum had suggested Spain, and which here approximates a fantasy France. Remarkably, given the confined quarters in which the action transpires, Hesketh’s camera placement prevents the viewing experience from becoming claustrophobic. The accomplished cinematography of Miquel Inti Canedo is subtly high gloss, while the editing of Avila conjoins the Then and the Now,and blurs the line between the real and the fantasized. The soundtrack is authentic, consisting of a 17th Century French marriage song with an appropriately dark undertone, which is itself counterpointed by/against a background of songs from the French Revolution. This contrast serves to place the action precisely at the historical interection where the Enlightenment and Romanticism collided.

Hesketh’s approach reimagines film acting as a form of performance art and is blessed by an exceptional cast in realizing this.

As the Marquis, Jac Avila himself clearly takes pride in his handiwork and, thus, convinces us that he does, indeed, “delight in what (he) is addicted” to. He “removes the veils of modesty”, relishing his role for what it offers.

As his performance partner, Hesketh discovery Mila Joya, a sultry Hispanic with luxurious hair, is subjected to all manner of cruelties, both psychological and physical. Her eyes “beg for more” with supplicant silence, even as she bellows with blood-curdling, agonized screams before being broken.

A reoccurring theme in this production company’s work, the criticism of organized religion, is voiced by having the title character parrot De Sade’s thoughts on the subject.

Deeply disturbing and completely uncompromising in its central theme, this film, distributed by Vermeerworks, is impossible to forget.